TOPIC 2.1 African Explorers in the Americas

The Adventures of Juan Garrido: “You make the DECISIONS!” Activity

LO 2.1.A Explain the significance of the roles Ladinos played as the first Africans to arrive in the territory that became the United States.

LO 2.1.B Describe the diverse roles Africans played during colonization of the Americas in the sixteenth century.

Objective: Students will analyze the life of Juan Garrido to understand the variety of roles and the agency of early Ladinos in the Americas in order to see the change over time for individuals of African descent in American societies between 1500 and 1865.

“I, Juan Garrido, black resident of this city [Mexico City]…”, Garrido’s letter to Charles V, 1583

“…the particularities of how we experience the Black Atlantic were made by human decisions, humans who exploited useful categories of difference for political purpose. The narratives of Black Spaniards like Juan Garrido the Conquistador…offer tantalizing hints to roads that were explicitly closed by the contingencies of a future time.” - Marley-Vincent Lindsey, Brown University

Notes

Juan Garrido’s story illuminates the significance of the role Ladinos played in the early colonization of the Americas, as well as the diverse roles that people of African descent played during this era. Reflecting on Garrido’s life is a great way to “set the table for unit 2” and will help start reflection on topics like the complexities of the African American experience, the invention of "Blackness," resistance, agency, and survival. A meaningful lesson for Topic 2.1 will also be very useful scaffolding for students as they later grapple with the main ideas of Topic 2.9, namely that racial concepts and classifications evolved and emerged alongside definitions of status, but they were not a foregone conclusion in the history of the Americas. Throughout this class we will study and discuss the development of Black identities over time. Mansa Musa was not Black in Period 1; he was the King of Mali. “Blackness” was invented during Period 2. Juan Garrido’s letter to King Charles V is the first documentation of a man of African descent in the Americas who refers to himself as “Black.” What did that mean for Garrido? Certainly, not the same thing this would come to mean in colonial and later U.S. legal codes, or to David Walker, or Sojourner Truth, or Marcus Garvey, or Maya Angelou.

In order to highlight the range of options open to Garrido, the “first African American” in the 16th century, I created a simple “Choose Your Own Adventure” style activity. My students had a lot of fun with it, which led to meaningful class discussion.

Lesson Description

Class starts with a “thought experiment.” (3 minutes) I tell students:

“You are about to learn about the life of the first African who arrived on the shores of what is today the United States. Take a moment to visualize what that might have been like—what he might have experienced and the emotions he might have felt.” (Pause for 40 seconds)

“Now, I am going to ask you to consider two famous people from the early days of colonial history of the Americas. The first is Christopher Columbus. Take a moment to reflect on what you know about him. What was his legacy? How did he view the Americas? What did the Americas mean for him?” (Pause for 40 seconds)

“Now I want you to think of another famous person. Think of any famous person of African descent who lived in the Americas between 1500 and 1865. Take a moment to reflect on what you know about this person. What was their legacy? How do you think they viewed life in the Americas? What did the Americas mean for them?” (Pause for 40 seconds)

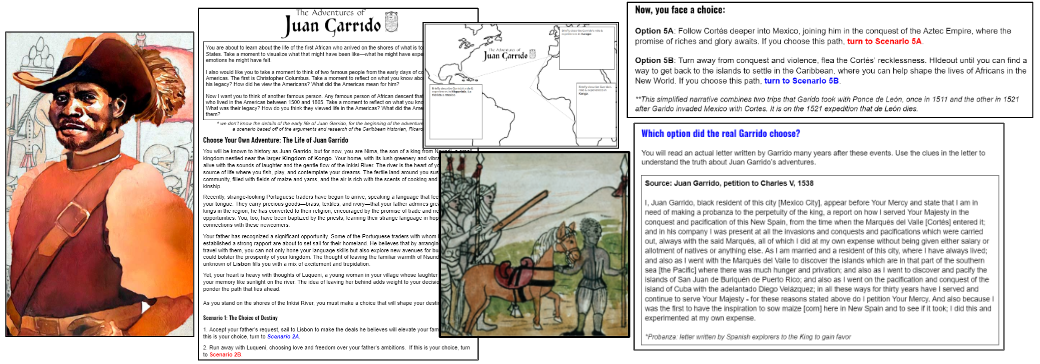

How it works: Juan Garrido's “Choose Your Own Adventure”

(See printing instructions below)

This takes about 20-30 minutes to get an entire class of 30 through the five scenarios as they choose their own adventures.

I place all the printed scenarios on a table at the front of my room so that I can easily find them when the simulation begins.

Hand out a copy of the map to each student. This is for them to take brief notes throughout the adventure. These do not need to be comprehensive.

I put students in groups of 2 or 3 and then hand out page 1 (of the “The Adventures of Juan Garrido”) to all students. Students should read the first scenario* and make a decision. Will they go with 2A or 2B? When they are ready, they should send a representative up to me at the front table. Be prepared to tell me WHY you chose this option (I ask them the first time through, but then it usually gets too busy, and I just give them the scenario they request).

No matter what choices the students make, they will find themselves in the Iberian Peninsula and then the Americas. They will all encounter Juan Ponce de León and Cortés. They will have the option to form alliances or to become a fortune-seeking colonizer.**

All students will end with the final scenario of 5a (the actual historical path of Garrido in which he participates in the conquest of the Aztec Empire) or 5b (which is historical fiction that anticipates the role of later resistance fighters and Maroon community leaders). Either way, every student ends with the 2.1 required sources, “Juan Garrido’s Petition to King Charles V.” Students are prompted to read the document and infer whether the real Garrido made the same decisions as they did.

When students are finished, they must find another group of 2 or 3 (making groups of 4-6), grab a die, and begin their “Dice discussion.” (Instructions are at the bottom of the page: they roll the die, discuss 3 of the questions, and use the die to choose a presenter to share out with the class). If students finish the dice discussion, tell them to work on their 2.1 vocab while they wait for the whole class discussion.

When should you move to the whole class discussion? I wait until every group has at least had time to discuss one dice discussion question. At this point, one or more groups will likely have concluded their discussion and moved on to working on their vocab. Then I bring the whole class together and discuss. I make sure to highlight that Garrido’s true origin story is unknown, but the letter he wrote to King Charles V is a real primary source and a key required source for Unit 2. Then I let them take it from there. If no one brings up question #3, I make sure to highlight this issue (see my notes at the bottom of this page).

The next day, I start with a warm-up reading discussion from a blog source on Garrido’s story and the invention of race in the American colonies. Students should read the source and discuss it with their table. Make sure to hit the last question as well. Would you use a source like this in your final APAFAM presentation? Why or why not?

NOTE ON HISTORICAL ACCURACY

* We don’t know the details of the early life of Juan Garrido. We do not know Garrido’s original name. There is no documentation of how or why he ended up in the Iberian Peninsula. The beginning scenarios of this adventure are based on APAFAM class content for “1.11: Global Africans” and the musings and research of the Caribbean historian Ricardo Alegría. The essence of Topic 2.1 is that Ladinos played a significant role in the early era of colonization of the Americas, and they filled a variety of roles in society. This experience contrasts with later eras of history after the concept of race is cemented through colonial legal codes.

Printing Instructions

(Yes, this is a lot of printing, yes, there will be some copies that go unused. Yes, you could just post this online and be more environmentally friendly and save some hassle. BUT, I love choose your own adventure lessons and I have found engagement and lesson success to be significantly increased with paper copies that students are required to discuss, then get up and come to me for the next scenario of their choice. So, I say: print it!)

Make a copy of the map for each student.

“The Adventures of Juan Garrido” document printing instructions:

Make a copy of page 1 for each student. - single-sided printing

For pages 2-7 (“Scenarios 2A” through “4B”), make a copy for half of your class size. My classes were evenly split in their decisions, so I had enough for 1 for each student. However, you might likely run out of one scenario so save a few of each example and have groups share if it comes to that. - single-sided printing

Pg 8 and 9: Make enough for about 2/3 of the class. Back-to-back printing (This is the final scenario (5a) with the discussion on the back.) This will lead to having extra unused copies, but since this scenario includes a required primary source and the discussion question on the back, I want to make sure each student gets a copy.

Pg 10 and 11: Make enough for about 2/3 of the class. Back-to-back printing. (This is the final scenario (5b) with the discussion on the back.) This will lead to having extra unused copies, but since this scenario includes a required primary source and the discussion question on the back, I want to make sure each student gets a copy.

NOTE ON POTENTIALLY PUTTING STUDENTS IN THE ROLE OF A COLONIZER

** I would not create a similar activity for an AP World History class that puts students in the role of colonizing conquistadors because it trivializes the violent and oppressive nature of colonization and may cause emotional harm to students. Educators should focus on critical analysis and empathy-building approaches that engage students in understanding the complex impacts of colonization without reinforcing harmful power dynamics.

This leads to the question of why I could write that option for this activity. Here is my justification: Allowing a "Choose Your Own Adventure" activity for Juan Garrido is justified because it enhances student engagement and reflection in ways that traditional note-taking cannot. This format encourages students to actively participate in learning by making decisions, which deepens their understanding and emotional connection to the content. In the case of Juan Garrido, the lesson is not simply about historical possibilities but about exploring the lived experiences and agency of an African-descended man in colonial America. By engaging in Garrido’s journey, students are prompted to reflect critically on Black experiences in history. This approach helps "reframe" their understanding of African American history, fostering a deeper, more reflective learning experience, and challenging prior misconceptions about passivity or victimhood in Black histories, contributing to a process of "unlearning" ingrained narratives.

That being said, I always make sure that this is addressed in class. If no group chooses to share their reflection on discussion question #3 about morality or on #6 (the third Wild Card option), I make sure to comment on these in front of the class.