Theme: Migration and Settlement Over-Time

U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Policy: from 1790 to 2026

THEMATIC FOCUS Migration and Settlement: Push and pull factors shape immigration to and migration within America, and the demographic change as a result of these moves shapes the migrants, society, and the environment.

Objective: Students will be able to explain the the cause and effects of major changes in American immigration and naturalization policy and enforcement.

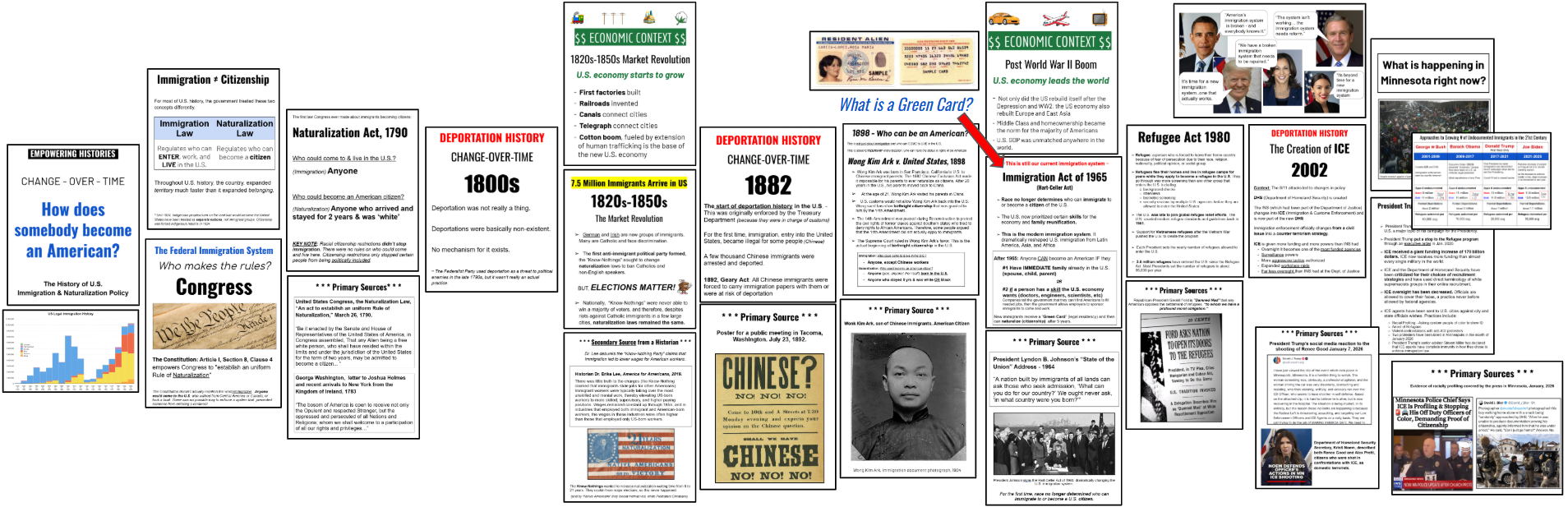

The GIANT IMMIGRATION POLICY CHANGE-OVER-TIME Timeline

With increasing student questions and apprehensions surrounding changes in immigration policy and enforcement, I decided to lean into my students’ intrinsic interest and curiosity about the topic. I took all of the immigration resources I have collected and lessons I have created over the years through old grad school notes and my partnership with the brilliant immigration lawyers and educators at the Immigrant History Initiative and put them into one giant timeline / gallery walk.

This comprehensive timeline begins by defining the differences between “immigration” and “naturalization” and then leads students from the Constitution to the first Naturalization Act of 1790. It asks: What were the original immigration and naturalization laws?

Who could come to live and work in the U.S. in 1790 (immigration):

Anyone — it would not be possible to be considered an “illegal immigrant” until 1882.

Who could become a citizen in 1790 (naturalization):

Any man who came, stayed for two years, and was classified as “white.”

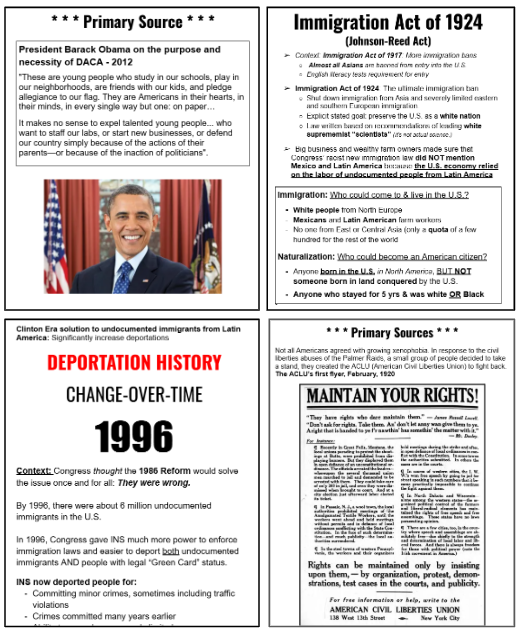

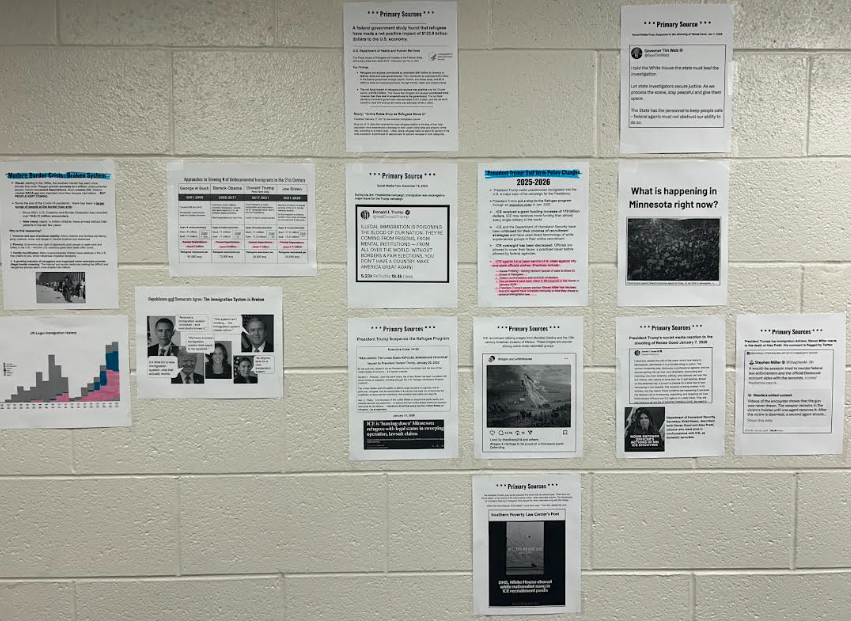

The timeline is 66 pages long (it took my 55-minute prep hour to tape it up in the hallway, plus an extra five minutes with a highlighter to color-code a few things: “Economic Context,” “Policy Changes,” and “Deportation Over Time”).

The timeline covers thinking about immigration policy from George Washington to Stephen Miller and explores immigrant stories ranging from Wong Kim Ark, whose legal battle led to the enshrinement of birthright citizenship in 1898, to Selamawit Mehari, a legal resident refugee from Eritrea who was arrested by ICE without cause or warning at her home in Minneapolis in front of her crying children in January 2026.

The real magic is in students’ natural curiosity and interest in the topic! I created a handout and a short warm-up, but the sources do the real heavy lifting. I spent two days answering student questions and listening to my students discuss and process the material with one another.

My In-Class Procedure

You could use the timeline in many different ways (I’d love to hear to if you come up with your own way to use the materials!) I am leaving my own set of the timeline up in the hall next week so that some English teachers can utilize them for their own discussion and assignment.

Step 1: Set the Tone Before the Bell

I have the first slide displayed on the screen as students enter the classroom. Conversations and questions start immediately, before the bell even rings.

When the bell rings, I ask:

How many of you have been following what’s been happening in Minneapolis?

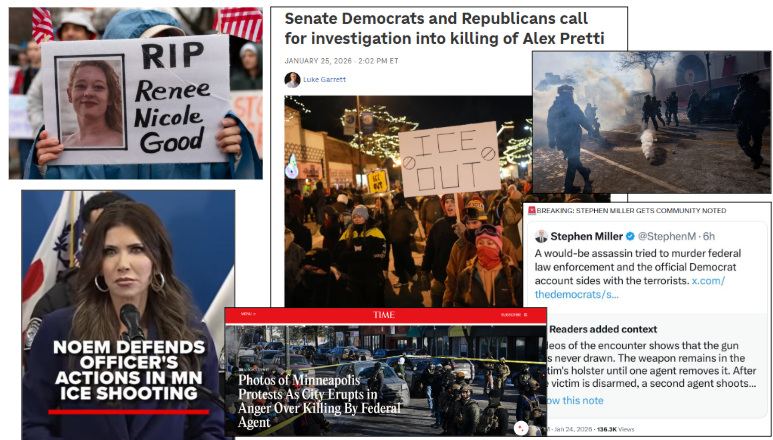

How many of you have seen something about ICE, Minnesota, protests, or the shootings of Renee Good and Alex Pretti?

In every class, every single hand goes up. While there is a wide range in how much students know, every student has seen something about this through their algorithms. This moment matters, this is the modern legacy of the civil rights struggles, federal vs. state power conflicts, and debates over American identity we’ve been studying all year. Because students are encountering this through social media, it’s essential to create a safe space where they can slow down and process together.

Step 2: Ground Students in Shared Facts

I briefly go over a few bullet points outlining the basic facts and timeline behind the increased tensions over immigration enforcement in Minneapolis. The goal here is not to debate, but to make sure everyone is working from the same factual foundation.

Step 3: REAL WORLD Document Analysis

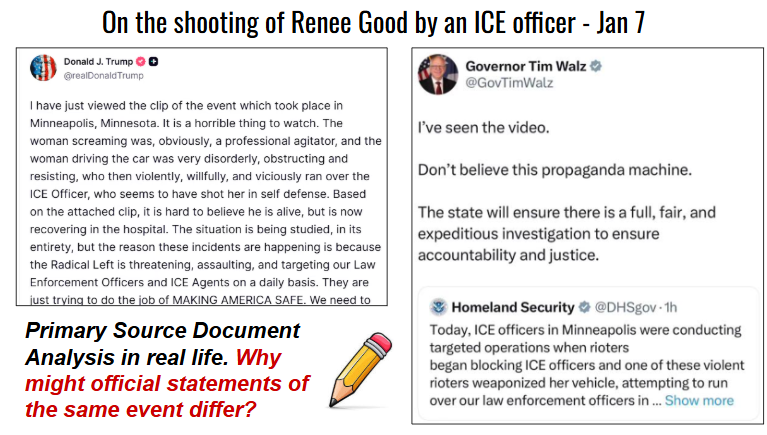

Next, I project President Trump’s and Governor Walz’s social media posts from January 7. I ask students to think and write about why two elected officials could have such dramatically different interpretations of the same event.

I tell them explicitly: this is “Y” document analysis (SPY method) happening in real life. Same moment, different perspectives, different goals, different audiences.

Step 4: Clarify Key Vocabulary

Before heading into the hallway, I briefly review the difference between immigration and naturalization. This step is quick but important, it ensures students don’t conflate the two as they move through the historical policies on the timeline.

Step 5: Staggered Entry to the Timeline

I split the class in half just to stagger them in the timeline walk.

Group 1 goes directly into the hallway to begin the timeline.

Group 2 stays in the classroom and completes a short set of AP-style multiple-choice practice questions on the Chinese Exclusion Act.

Because the timeline must be experienced in chronological order, staggering groups prevents overcrowding at the earliest documents and allows students to engage more thoughtfully.

Step 6: First Pass Through the Timeline

Students are instructed to take their time walking through the entire timeline once. I emphasize that this first pass is about noticing patterns, questions, and shifts, not rushing to complete the handout.

Step 7: Deeper Policy Analysis

After completing the timeline, students should be able to answer the questions on the front of the handout. Then students choose one immigration policy from the 18th through the 21st century to analyze more deeply on the back of their handout. This section asks them to do a brief comparative analysis, connecting that policy to others they saw on the timeline.

Step 8: Flexible Pacing and Processing Time

Some students want, and need to talk, ask questions, and do careful analysis for two full class periods. Others finish the timeline in about 25 minutes; those students are allowed to shift to Unit 6 Gilded Age review activities.

It is critically important that all students understand how the current immigration system developed, but it’s equally important to recognize that some students need time to process emotionally and intellectually. For that reason, giving this lesson two class days is not a loss of time, it’s time well spent.